Six reasons people think they don’t need one when they really do

In short, everyone can benefit from having an estate plan. There is no specific income threshold or criteria to meet in order to need an estate plan or gain the benefits from having one in place. Your circumstances and personal wishes are what guides how estate plans are created, but the specifics of your life shouldn’t prevent you from realizing the benefits of having an estate plan.

This article explains under what specific circumstances you might need an estate plan and why the reasons you think you might not need one aren’t always true.

_______________________________________________________________

For many people, the word “estate” in estate planning conjures up images of a mansion with servants and grand staircases and probably a stable out back. Most people don’t see themselves in those images, which means they relegate estate planning to the über-wealthy. The result? You likely have formed a few misconceptions about who needs an estate plan, confident in your belief that it’s simply not for you. But that’s a costly mistake many people make. Here, we bust six of the most common myths about who needs an estate plan.

Myth 1: Not me, I’m not rich enough.

Do you have a savings account? A car? A dog? These are not the trappings of the rich and famous, but they are parts of your estate that will need to be taken care of or find a new home when you die.

Reality: Yes, you have an estate, which is really just a fancy word for all your stuff. There is no minimum net worth that triggers a need to create an estate plan, but rather a series of decisions you can choose to make. Otherwise, you will let laws drafted long ago determine where your stuff should go and a judge who has never met you might decide who should manage your affairs and take care of your kids. You may already have designated a beneficiary for some of your accounts—your 401(k) and life insurance, for example. But that’s just a first step toward a plan; estate planning is the best way to direct how the rest of your property and possessions should be divvied up.

Myth 2: Not me, I’m not old enough.

We get it—lots of people put off estate planning because it makes them confront the idea of death. But guess what? It’s going to happen to all of us, and none of us know when, so it’s better to be prepared, right?

Reality: You can start estate planning as soon as you turn 18 (and in some states, even younger!), but the real trigger is when you start acquiring things—money, real estate, vehicles, collections—that you want to protect after you die. And, of course, having kids is one of the biggest reasons people start thinking about estate planning.

Even in their 20s, most people have possessions they’d like to see passed on to family members or other loved ones. You may be worried that no one in your family would know to give your pets to your neighbor or friend, rather than surrender them to a shelter. Or, if something were to happen to you, you feel strongly that you would want certain family members (but not others) to manage your affairs or make medical care decisions for you.

Myth 3: Not me, I don’t have any valuable property to pass down.

Just because you don’t own real estate doesn’t mean you don’t need an estate plan.

Reality: Often value is in the eye of the beholder. Maybe you and your favorite nephew have always shared a passion for model trains and you would want him to end up with your train set that he always admired. Or you would like to make a last cash gift to your favorite charity as part of your legacy. You can include instructions in your will about sentimental possessions too, ensuring they are preserved and appreciated by future generations.

Myth 4: Not me, my family knows exactly what I want to happen when I die.

Do they really? Are you sure? Do they know your feelings about organ donation, and would they respect them? If your family situation is calm and uncomplicated, that may be true. But that’s not most of us.

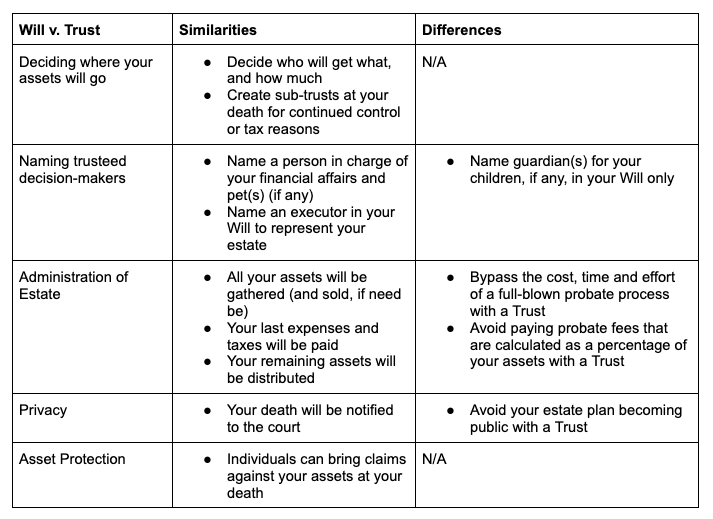

Reality: Making an estate plan is a gift to your loved ones that protects and provides for them while clearing up any confusion about your wishes. If something were to happen to you, it will be an upsetting time for those who step in to make the toughest decisions on your behalf. There could be disagreements about your treatment and care, who should sign paperwork on your behalf, and where your stuff will end up. When you take the time to put instructions into documents like an advance health care directive, a financial power of attorney, and a Will and/or Trust, you eliminate second-guessing and free your loved ones in making those tough decisions.

Myth 5: Not me, I don’t have kids, so I don’t need a Will.

Writing a Will that designates guardians for minor children is a commonly cited objective for estate planning, but it’s not the only one by a long shot.

Reality: If you die intestate (without an estate plan), your possessions and property will pass to your children or spouse in some proportion that varies by state law. But if you’re single and don’t have kids, then it actually makes it more complicated to decide what to do with your stuff. Depending on the state, all of your stuff might go to your parents, otherwise your siblings. If you want anyone else – a nephew, friend or charity – to receive anything from your estate, however small, you need an estate plan.

Myth 6: Not me, I’m not dying anytime soon, so I don’t need to worry about estate planning now.

Reality: In addition to being prepared for the unexpected, there’s a very important part of estate planning that many people forget about because it covers what happens when you’re alive. Signing an advance health care directive and financial power of attorney are two estate planning steps that allow someone else to make decisions on your behalf and grant signature authority over your affairs. The advance health care directive, when it includes a living Will, also clarifies your wishes for the type of medical care you want to receive if you are unable to make decisions for yourself or communicate for yourself.

Everyone can benefit from an estate plan regardless of circumstance. That doesn’t mean everyone’s estate plan will look the same, it just means that the answer to “who needs an estate plan” is… me.

Ready to get started?

We can help you create, manage, and visualize your estate plan using our comprehensive and secure platform, without needing any outside help.